Universal’s Dracula (1931) isn’t the first American vampire movie. But Bela Lugosi’s Count Dracula established the paradigm for how we expect a “Dracula” to be. His Central European accent. The predatory mannerisms and his cape, which he uses almost like bat wings. Now and then, a director emerges who challenges and expands our expectations of the genre. Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992) comes to mind. Robert Rodriguez and John Carpenter do, as well. And now, so does Ryan Coogler’s Sinners (2025).

It is a supernatural horror set in the 1930s Mississippi Delta. Twin brothers return home, trying to leave their troubled Chicago past behind them. The plan was to open a jukejoint with stolen booze and money from Al Capone and other Chicago gang outfits. A place for social gathering. Nights full of dancing, drinking, gambling, and listening to the blues. Unbeknownst to them and the people of their hometown, it won’t be the kind of night everyone expects.

Sinners is more than a vampire movie. It’s a coming-of-age story, and a love story. It’s a tale from deep in the sharecropping South. The Great Migration. A story of becoming American and Black American. One long blues song. Told behind the backdrop of supernatural horrors unfolding throughout one night. It’s very ambitious to weave so many concepts into the fabric of a vampire blockbuster. Very cerebral at that. But with writer-director Ryan Coogler, has there ever been any other way? He’s achieved it four times before, each with award-winning efforts. With Fruitvale Station, Creed, Black Panther, and Black Panther: Wakanda Forever. Sinners establishes expectations and standards for Coogler as a brand. And not only for Coogler but also for his longtime trusted collaborators.

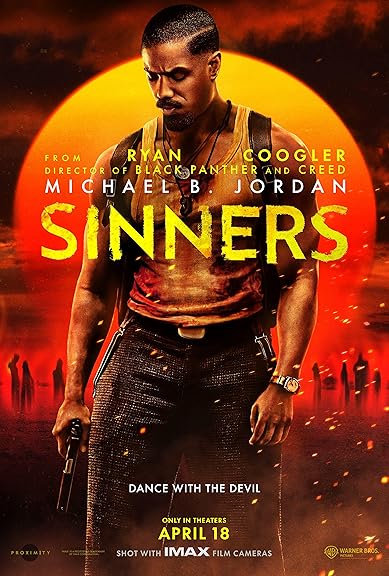

Variety reported that it went from pitch to production in about 90 days. It went from filming in IMAX to screens in 11 or 12 months. It’s a feat that doesn’t happen without collaborator Michael B. Jordan. In Sinners, he stars as the twin brothers Smoke and Stack. He and Coogler are like director-actor duo Spike Lee and Denzel Washington. Jordan starred in several films and television shows that Coogler did not direct. But whenever he works with Coogler, we expect the two to create something amazing. And fast. Like Quentin Tarantino does with Uma Thurman and Samuel L. Jackson. Or Wes Anderson with Johnny Depp and Helena Bonham Carter.

Sinners expands not only American cinema but also our vampire genre. Many European immigrants preserved the classical music tastes of their native land. So, we Americans recognize blues as one of the earliest music genres. It’s foundational. The chronicling of an evolving African diaspora told through songs. Stories of sadness and sometimes supernatural situations. Surviving circumstances like slavery and racism to define dignified Blackness in America. If you’re a music fan like myself into all types of cool shit, you know the real-life story of Robert Johnson. The legend goes that he sold his soul to the devil in exchange for success as a blues musician.

Coogler casts newcomer Miles Caton as “Preacher Boy,” the paternal cousin of Smoke and Stack. He’s the son of Jedidiah, a preacher played by real-life musician and poet Saul Williams. He sings at his father’s church but can’t resist the call of the wild, life as a blues singer outside Mississippi. He has an extraordinary gift, a voice that can “conjure spirits” and “pierce the veil between life and death.” Sin in the Bible is about free will. It’s about recognizing that you’re choosing how you live your life and how you choose to use your gifts. Rushing their grand opening, the twins offer Preacher Boy a chance to showcase his. “Sinners” is an appropriate title. And Coogler’s casting of Caton to convey this powerful metaphor on-screen was deliberate.

Coogler enlists many of the same talents behind the scenes as well. We’ve come to expect not only Jordan but composer Ludwig Göransson. Caton is a singer and songwriter. He’s toured with H.E.R. and performed at the Grammys and Academy Awards.

The guy can sing. And with him taking tips from Jordan’s past experiences working with Coogler, we now know he can act. He delivered the film’s message about attracting supernatural, malevolent forces through your artistry. Caton’s powerful performance of the original song, “I Lied to You,” sells the movie. If there are Oscar nominations for the film, this song by Ludwig Göransson and Raphael Saadiq will be one of them. Also, the closing credits song, “Sinners,” by Rod Wave.

Coogler’s choices mark more than his deliberations. They also testify to his faith in the abilities of those he collaborates with to meet our expectations of him as a filmmaker. Hailee Steinfeld and Wunmi Mosaku are the magic behind Michael B. Jordan’s dual roles. Hailee Steinfeld delivers the white person comfortable in Black spaces role very well. The role was a considerable gamble for both Coogler and Steinfeld. It evokes inherent minstrel resonance and Blackface provocations. But in Oakland, California, people like her character have and do exist. Mannerisms, accents, and idiosyncrasies. A comment on X bothered me: a guy accusing Coogler of selling out. But the guy likely doesn’t know about the real Oakland. He’d know that Coogler likely grew up around white people like Steinfeld’s character.

Steinfeld isn’t a stranger to period pieces or exaggerated accents. She played 14-year-old farm girl Mattie Ross in the 2010 remake of the Western True Grit. The film maintains a “Certified Fresh” rating of 95% percent on Rotten Tomatoes. But performing a “soulful” white person in a Black space is daring. It’s not James Franco’s rapper, drug hustler, and gun seller, “Alien,” in 2012’s Spring Breakers. Her role is a white girl in the 1930s “Birth of a Nation” South who is unapologetic about being in Black spaces. That’s brazen. And as Sinners mentions, it can cost a Black man around her castration and his life. Insane.

The twin Stack is the Black man bold enough to. He’s the opposite of his brother, Smoke, who loves a Hoodoo practitioner named Annie. In real life, Hoodoo draws from Ifá, a traditional Yoruba religion. Wunmi Mosaku portrayed Ruby in HBO Max’s supernatural series Lovecraft Country. It, too, deals with race and what it means to become a Black American. Mosaku is British of Nigerian descent. Her character, too, is a considerable risk for herself and Coogler. But a level of transcending mimesis explodes when she’s on the screen. She’s among my wife and I’s favorite rising stars.

On any given day, if you ask me what I identify as I’d likely tell you “Black American. Black mixed with Black.” But it’s a reactionary response. I affirm a space and the right to exist as I am. My genetics are 50% Nigerian (Port Harcourt Igbo), and I’ve traced and found my ancestors. I’m also about 20% Irish. Northern, the Republic of Ireland, they actually reached out to me. Then, Carribbean: Trinidadian and Jamaican. Native American and due to the fact my grandmother owns historic land in the South. Her husband’s father, my great-granddad, was a Harlem Hellfighter. My paternal side is among the first free and homeowning Blacks in New York City since the 1700s.

Like in the film, my maternal side reminds me of Mosaku’s characters. My American Blackness is a space that I affirm and protect. I can only imagine what they all went through that made the Black that I am possible. They also descend from River Parishes and Greater New Orleans Creoles. As in Sinners, this demographic covers a large swath of land. It includes the Mississippi Delta. And if you’re into cool shit like myself, Voodoo priestess Marie Laveau hails from the region. Also, civil rights activist Dr. Ernest “Dutch” Morial. He became New Orleans’s first Black mayor.

Watching the mimesis Mosaku’s experiences with Black American roles is enjoyable and evoking. Each time, she experiences the responsibility we Black Americans owe our ancestors. Their travels. Their experiences and perseverance. It’s the blues. It’s American. As an actress, she delivers every time, and as a human being, the opportunity has intrinsic value. I’m sure it’s exhilarating to have a chance to reenact these experiences. If you pay close enough attention, as an actress, you can see how careful Mosaku is with this.

Imagine the courage and bravery of a Black American soldier to protect her. In Sinners, that’s the other twin, Smoke. Yes, we’re still reviewing a vampire movie. But the point is to look at how much history Coogler packs into a 138-minute film shot in IMAX. The inspiration comes from Coogler’s real-life uncle, James. He’s from Mississippi in the same period as the film. Coogler grew up hearing James listening to old blues records. Sinners is the writer-director’s first original feature. It is his first film that isn’t based on real-life events or preexisting IP. I’m only a fan and still high off the visceral connection the film evokes. The poignant force that tugs at you, reminding you of your history and roots.

Jack O’Connell plays Remmick, an Irish drifter. He reminds viewers of the oppression Irish people once experienced. He yearns for a world where people exist as one. Again, I’m part Irish, and on official documents, there are interracial unions in my family. Consensual. Like moving to states where their marriage was legal and where they could be together in public. People accusing Coogler of selling out saddens me. This means that not enough people know American history.

To dismiss Li Jun Li, Yao, and Helena Hu as token Asians would also sadden me. Chinese history in Mississippi goes back to the post-Civil era. Its first wave of immigrants came from the Sze Yap region of Southern China as paid laborers. With Blacks becoming sharecroppers, they replaced the freed slave population on plantations. Soon, they established themselves as merchants among both Black and white communities. They boosted Mississippi’s economic development.

Every cast member on screen serves a purpose. Delroy Lindo is a legend to me. The emotion he brings to characters, good or bad, is irreplaceable. He plays musician Delta Slim, who was once part of a chain gang. At this time, it was modern-day slavery. He likely self-medicates his PSTD with alcohol. He manages to convey the film’s plot in every scene. Especially with lines like “white folk like the blues just fine. They just don’t like who makes it.” He is also a legend in the film, and he feels his responsibility is to impart his wisdom to the young Preacher Boy.

As mentioned, some directors have challenged and expanded our expectations of the genre. After all, it’s still an American vampire movie we’re talking about. But Coogler wove these intricate historical themes and Black folklore into its fabric. There are inextricable rules and tropes we expect American vampires to follow. Watching the supporting cast do this in a Black way makes Sinners a Black horror. That doesn’t happen without 8mile’s Omar Miller as “Cornbread.” Or The Woman King and The Batman’s Jayme Lawson as Pearline.

In the end, I felt bad for the people leaving before the mid and post-credit scenes. As if the 130-something minutes weren’t enough, Coogler gives us more magic. Sinners is likely to be a top contender for movie of the year. At the least, there’s no doubt it’s on its way to becoming a cult classic. With Sinners, Coogler took American vampire cinema where it’s never been. He established his name as a Hollywood brand and the Black director of our times. Comparatively, Spike Lee and Denzel Washington have given us so much, and the duo are still providing us with more. But for me, as a grown-up millennial, Coogler and Jordan seem more than ready to take up the mantle.

Leave a Reply